By Donald Mattersdorff

Hertha S. Mattersdorff died on December 26, 1986, at the age of 87, in Beaverton, Oregon. Wife, mom and grandma, she was a businesswoman and a salesperson who led two distinctly different lives on two different continents.

She was born as Hertha Sara Sluzewski in Berlin in November of 1899. Her father was a lawyer and her mother kept house and raised the children. She had an older brother, Curt, who later became a barrister in London. Hertha was a teenager in Berlin during World War I. She did not go to college. She received some musical education, although we don’t know how much or from where, and retained a lifetime love of music, especially German classical music, including opera. She appreciated good etiquette and good posture, and pestered her family for years on these topics.

Hertha, age 5

Hans and Hertha, Early 1920s

In 1920, while vacationing in Bad Gastein, Austria, the Sluzewskis were seated for dinner at a table next to the Mattersdorff family. The Sluzewskis were a rather jolly group who laughed a lot, often too loudly, and the Mattersdorffs found themselves involuntarily eavesdropping on the conversation and laughing along. Before long, they began to chat, and then they pushed the tables together and created a single party. That’s how Hertha met Hans Mattersdorff.

They married on July 9, 1922 in Berlin, and were separated only by his death in 1954. The Mattersdorffs owned Bankhaus S. Mattersdorff, a regional bank with two branch offices and 30 or so employees, which was locally well known for small business finance in Dresden. When his father died in 1921, Hans, then aged 35, took over as the fourth generation in his family to manage the bank. He was tall but gentle and soft-spoken, good with numbers, but seemingly not well suited to the rough and tumble of business. He spent the next eighteen years trying to live up to the stern expectations of his father, largely unsuccessfully, though under very difficult circumstances.

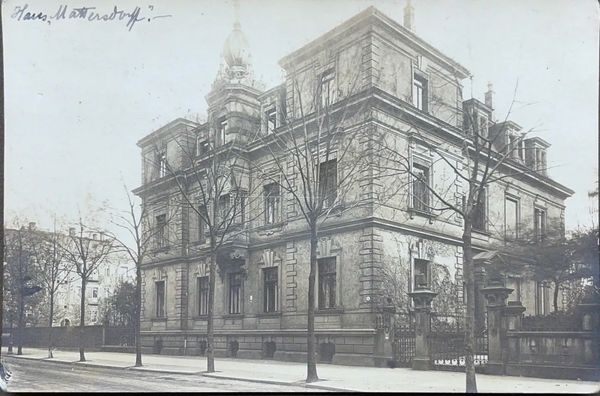

The family lived in a large home at Reichenbachstrasse 14, on which site today sits the Ludwig Reichenbach Elementary School. Hertha moved in and took over as lady of the house, with maids and (later) nannies, and a groundskeeper to manage. Hans and Hertha’s first son, Werner, was born in July of 1923. A second son, Guenter, arrived in November, 1926. According to family legend, Hertha managed the household tightly, keeping the kitchen cabinets locked and the keys tied around her waist. By all accounts, Hans and Hertha were happy together. The troubles of the day notwithstanding, their future looked pretty bright.

The House at Reichenbachstrasse 14, Dresden

The 1920s were a time of turmoil in Germany. In the early 1920s, Germany suffered one of the largest hyper-inflations ever. Between 1918, when Germany surrendered World War I, and 1923, the value of the Deutschmark fell one trillion-fold. Men pushed wheelbarrows full of paper money, and used it for kindling. Few businesses struggle more with inflation than banks do. (Bankers prefer a hard, stable currency for a good reason.) Nothing in his experience prepared Hans for this. How he kept the business afloat, probably by investing heavily in gold, has been lost to history. He paid his employees every day at noon, so that they could race out on their lunch break to shop before the currency collapsed even further. The bank experienced a serious impairment of its capital, forcing Hans to take a partner. Hans suffered a lot of stress just trying to keep the doors open, which caught up with him in later years.

Prices stabilized in 1924 and Germany recovered its prosperity until 1929, when stock markets crashed globally and ushered in the Great Depression. Political turmoil returned. In 1932, at the depths of the Depression, Germans elected Adolf Hitler as Chancellor. He took office in January of 1933 and immediately began to persecute Jews, mildly at first, but more viciously as time passed.

Numerous members of the family, including Hans' sisters and Hertha’s entire family, emigrated from Germany and encouraged Hans and Hertha to do so also. But Hans resisted, somewhat stubbornly. He was a patriotic German, and thought of Germany as a civilized society which would turn from Naziism before long. Almost certainly, he did not want to give up on the bank which had carried his family’s name since 1850 and start a new life abroad.

Others saw the situation more clearly. Hans’ sister Lisa decamped for Zurich, Switzerland with her five children. When war broke out and Zurich still seemed too close for comfort to Germany, they moved again to New York. His youngest sister moved to Brazil.

Hertha’s brother, Curt, saw the future especially presciently. Curt used his position as business manager of the Berlin Opera Chorus to smuggle cash into Switzerland. He hid the money in the toilet tank in the bathroom on the train. After German border guards had searched everyone’s bags and the train had advanced safely into Switzerland, he retrieved the money from the toilet and took it to the bank in Zurich, where he kept a numbered account. He made several such trips under the guise of business for the chorus, risking arrest and worse each time. He then booked passage for his family, including his elderly mother, to England. His wife wanted to move to Belgium or The Netherlands. But Curt would hear none of that. He insisted on placing the English Channel between himself and Hitler. Despite some tense moments during the London Blitz, they lived the rest of their lives happily in the suburbs near Hampstead Heath.

Hitler ceased making reparations payments to the Allies of World War I. He redirected the payments towards rearmament, building a formidable military, and created in the process something of an economic recovery for Germany, such as did not take place elsewhere in Europe. Though elected to office with a bare plurality of votes, his popularity rose, allowing him the latitude to abolish elections, establish a secret police, burn down the Reichstag (likely) and take dictatorial control. After twenty years of tumult, Germans craved stability and a restoration of their lost prestige, and Hitler appeared to give it to them. The persecution of the Jews intensified.

Almost upon taking office, the Nazis undertook to “aryanize” the economy. They dismissed Jews first from government positions, then from schools and universities, and then from shops and all private enterprises. Jews had no avenues for work. The Nazis were very keen to aryanize banking. But a lot of banks had Jewish ownership, and the Nazis were sensitive to the risk that if they moved too aggressively, they might disrupt the financial system. So they proceeded somewhat more slowly and carefully in banking than they did in other sectors of the economy*.

Hans and Hertha were forced to wear the Star of David on their clothing when they left the house, and the streets of Dresden became hostile. They spirited their boys out of the country to a school in Switzerland, and then returned to keep things together at home. The atmosphere was tense.

In later years, Hertha spoke very infrequently, if ever, about this time. She mostly stayed at home, alone. Her own family had left Germany for England. Now her boys were gone. They never lived with her again. The servants left. With her husband under pressure at the office, she cleaned the house herself and had plenty of time to worry. Her star had fallen quite low from where it stood in the 1920s. It must have seemed to her that things could not get worse.

But they could, and they did. By 1938, Hans felt strong pressure to sell his bank to an Aryan-owned firm. He eventually negotiated a deal with the Sächsiche Vereinsbank (which itself later merged with the Dresdner Bank). We don’t know the price to which the parties agreed. But this was a forced sale, as everyone involved understood, and the price certainly did not reflect the true value of the business.

That, as it turned out, did not matter. On the day that the deal was agreed, a small announcement of it appeared in the Dresden evening newspaper. That night, Hans and Hertha went out to celebrate at the home of the Breit family. The Breits were minority partners in the firm, and this sale freed them to emigrate also. No doubt they spoke of leaving Germany. Hans and Hertha returned home, and prepared for bed. At 11 pm, there was a knock at the door. It was the Gestapo, the German secret police. The agents had read the announcement in the paper. They arrested Hans on charges of hiding money and smuggling it out of the country, charges of which he was innocent, and took him downtown to the police station. He languished in a cell for three days, undergoing interrogation, and justifying his accounts to the police. Fortunately for him, no money was missing. The Gestapo forced him to sign all of his assets, including the proceeds from the sale of the bank and his substantial property holdings, over to the German government, with the understanding that he would leave the country as soon as he had concluded the sale. They labelled this an “emigration tax”. He left the police station with an exit visa but nothing of value to his name.

One can only guess at how he felt then. His life’s work and that of his three predecessors had just been destroyed. Most likely, he questioned his own choices, and probably felt guilty for the rest of his life. He had not suffered from lack of warning from members on both sides of his family. As the only member of the family who had maintained a faith in Germany, confident that it was too civilized for Hitler, he had bet disastrously, and lost everything. If he was angry also, as he had a right to be, he kept that to himself.

He returned home to Hertha, but they could not leave Germany yet. Hans had to close the deal with the Vereinsbank and tie up all of the loose ends. In November of 1938, rioters looted and destroyed Jewish businesses throughout Germany. This was the Kristalnacht. The Mattersdorff Bank, now under aryan ownership, was not damaged. The Dresden Synagogue burned to the ground while firefighters looked on but did nothing. Hans and Hertha left Germany for Zurich in the summer of 1939. World War II began on September 1, at which point borders closed and very few further Jews escaped.

They picked up their boys and continued to Genoa, Italy, where they booked a voyage to America on the SS Conte Di Savoia. They arrived on Ellis Island in New York City on November 14, 1939.

With the hindsight of history, it is easy to see that these were in fact the luckiest events in Hans and Hertha’s lives. Their whole family got out of Germany. No Mattersdorff or Sluzewski died in a concentration camp or a gas chamber. In 1946, Dresden was bombed flat and all the properties which they had left behind were completely destroyed. The city became part of East Germany and remained under communist rule until 1989 - 56 years of tyranny.

The just-in-time exodus to America, accomplished under duress and only with a kick in the pants from the Nazis, was a miracle. In later years, despite their mistreatment and the theft of their property, Hans and Hertha took pains not to complain, certainly not publicly. They knew how lucky they were, and that millions had suffered much worse.

Hans and Hertha, May, 1950 in Beverly Hills

Upon arrival in the United States, their fortunes turned for the better. Although Hans and Hertha were almost penniless, they still had some connections. They found scholarship placements for their boys in boarding schools on the east coast. During a banking apprenticeship in his youth, Hans had visited California. Now they made Beverly Hills their home. The contrast between this town, with its sunshine and palm trees and movie stars, and grey old Dresden could not have been more stark. They adjusted, seemingly well. In time, they bought a small, Spanish-style bungalow on South Rexford Drive.

In 1940, Hans was 54. His most productive years were behind him. He could not hope to create a bank in the United States, or even to work in one. He took a job as a bookkeeper in his cousin’s camera shop and worked there almost until the end of his life.

But Hertha, aged 40, had more time. With no business experience, she found work as an Avon lady. It was her first job. Expectations were set rather low. To everyone’s astonishment, she excelled at it. Walking the streets of Beverly Hills, speaking limited English, and ringing the doorbells of total strangers, she began to rack up sales. She met many German-speaking refugees like herself. The old Sluzewski joie de vivre returned and she made friends and expanded her social circle. Selling Avon was fun. She and Hans attended the Los Angeles Philharmonic and socialized with their new friends. At home, sprinkled in with family photos, Hertha displayed certificates of sales achievement and membership in Avon’s Top Producers Club.

She accomplished these things in part by ignoring some of the rules of the game. In particular, she ignored a rule that representatives could not keep a supply of Avon products at home. No doubt, the company had good business reasons for such a policy, such as the need to make an accurate accounting of inventory. But the policy held representatives back. For each order, a representative had to fill out an order form, collect payment, and submit it to the company. The product would arrive a couple of weeks later, at which time the representative delivered it to her client, and inquired at the same time if the client needed anything else.

Hertha built her career breaking this rule. She kept a large commode in her house into which she stuffed every Avon product that could possibly fit. The trunk of her car held more - lipsticks and rouge and eye shadow in every possible shade and gloss. If a client called to say, “Oh Hertha, we’re going to the Hollywood Bowl this evening, and I’m out of lipstick. Can you help?”, she replied, “Just a minute, let me see.” She checked her inventory. If she found the product which the client needed, she returned to the phone to say, “Yes, I have it. I will see you in ten minutes.” At the client’s house, she delivered the product, filled out an order form and collected payment, setting a world record in the process for quick delivery (delivery prior to the order) which Amazon can’t touch today. When the replacement product arrived, she replenished her private stock.

Then, living frugally, she took every dollar which she could save and invested it back in the stock of Avon. She could observe first-hand how popular and how easy to sell Avon products were. Through the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s, the company roared ahead, and Hertha’s investment portfolio, consisting of one stock, did likewise. By the time that she died in 1986, though not yet as wealthy as she had been in Germany (not by a long shot), she was again comfortably well-off, the result of hard work, careful saving, and a simple yet successful investment strategy.

On May 10, 1954, at the age of 68, Hans suffered a heart attack and died. He had lived with high blood pressure for years. The stress of struggling to hold on to a difficult business, under the worst conditions which history can dish up, finally caught up with him.

Hertha adjusted to single life and carried on. She lived another 32 years as a widow. In the early 1960s, she became a grandma. Although her sons and grandchildren lived in Oregon and Maryland, Hertha continued to live independently in Beverly Hills, supporting herself, and enjoying the society of her friends of 30+ years. She bought a Buick Gran Sport with a V8 engine, a car so large that she could barely see over the steering wheel. But she had a solid business reason for doing so: she needed the trunk space.

Interestingly, in spite of her mistreatment by the Nazis, and in spite of the subsequent revelation of the Holocaust, Hertha remained proudly German. She drew a sharp distinction between Germany - a civilized nation with a long history of cultural accomplishment - the home of Beethoven, Brahms and Bach (or the Three Bs, as she called them) - and the genocidal Nazi regime which governed and drove it to ruin between 1933 and 1945. She returned to Germany numerous times, although never to Dresden. Then she detoured nostalgically, often alone, sometimes with family, into Switzerland, to St. Moritz and the village of Pontresina, to walk and rest and take in the mountain air, as her family had done in the olden days, when she was a child.

Hertha with her grandson, 1962

Seemingly, she was not lonely. She was comfortable in her own skin, and had a knack for making friends. Not everyone appreciated her, however. Hertha could be bossy. She had two daughters-in-law whom she liked to boss around (as they saw it). Both of them anticipated her visits with dread and looked forward to her departure with relief. But she was a good grandma who supported her sons and grandchildren whenever and however she could.

She was surprisingly good at ping pong, and could beat her sons and grandchildren into her sixties.

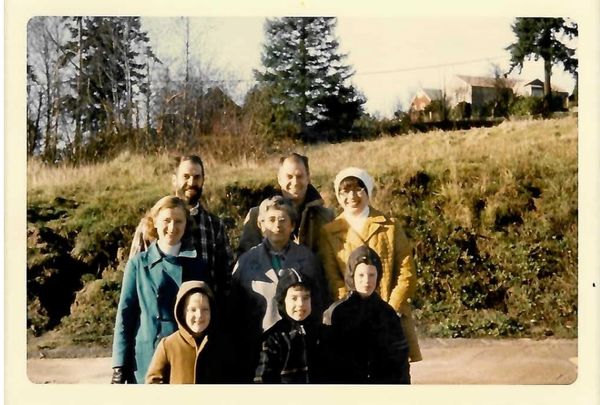

With her family, 1970

Eventually, time caught up with Hertha. She retired from Avon. By the late 1970s, many of her California friends had died. She herself declined, requiring the support of her family more than she had previously, and she moved to Portland, Oregon, to be closer to the family of her second son, Guenter. She lived in Terwilliger Plaza, but now, at age 80, did not participate in the community there. Although she had adapted very well to California from Germany, with increased age, she could not adapt to Oregon. It was almost a foreign country to her, representing a loss of independence and the life which she had built for herself in California. She sometimes spoke, nostalgically but unrealistically, of returning to Beverly Hills. She passed her final year at the Maryville Care Center in Beaverton, and died of pneumonia on December 26, with her son and family standing by.

She left a legacy of strong-willed independence and self-sufficiency. Although she was born into a comfortable upper-middle class family, and though she married into greater wealth, when Hertha’s fortunes turned down, she rolled up her sleeves and worked, without complaint, and with a flair for business which no one anticipated - no one except, just maybe, herself.

She embraced America, taking full advantage of the freedoms and opportunities which it offered, but also remained proudly German. She exhibited a pragmatic streak towards doing what needed to be done, be it for work or family, or just getting the car repaired, in a manner which was free of political views or resentment. She had seen for herself how politics and ideology could go badly wrong, and, especially in the second half of her life, she stayed entirely away from it. Better to support yourself, and to enjoy the company of your family and friends, and to do a little good here and there, in the brief time which you have in the world.

Only her immediate family attended her memorial service. A Unitarian minister who had never met Hertha gave a few brief and meaningless words (Hertha was not Unitarian). Then family members sat in a circle and told stories from her long life. She lived an eventful life, and experienced first-hand a lot of turbulent European history, and some less turbulent American history also. She had shown bravery when needed, not to mention adaptability, a certain level of ingenuity, and perseverance. These qualities guided her through good times and bad, and we had no shortage of stories to tell.

Endnotes

*Money and banking lay outside of Hitler’s circle of competence, and he knew it. In these matters, he relied on the advice of Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, the president of the Reichsbank. Schacht was technically not a Nazi. He held high banking positions in the Weimar Republic. But he was an anti-Semite who had no compunctions about serving Hitler or about aryanization. Schacht even proposed a scheme to use assets confiscated from Jews as collateral for international loans to the German government. Schacht was arrested by the Nazis after the attempt on Hitler’s life in 1944, and spent the rest of the war in concentration camps. After liberation from Dachau, he was rearrested by the allies, tried twice as a war criminal, and acquitted both times. He went back into banking and died peacefully at the age of 93. See Hitler’s Banker, by John Weitz, and Confessions of the Old Wizard, Schacht’s autobiography.

For Inquiries Contact Donald Mattersdorff

Copyright © 2024 The Life of Hertha - All Rights Reserved.